Several months ago, a friend and former lover, J, killed himself. Some weeks after that, a friend died very unexpectedly in his sleep. Since then, I have been trying to understand suicide, death and grief. I have kept a file on my computer where I’ve put down thoughts, questions, observations, measurements. I have tried several times to corral those fragments into something more coherent and complete, to try to reason through grief. These efforts have usually ended up deleted, or literally printed out and shredded.

Nonetheless the urge to write about it remained, and specifically to write about making sense of suicide, which strikes me as not a kind of death in the order of other deaths, and especially of the grief that follows. Necessarily, what I write below is also marked by that second death, too, less explicitly but no less deeply. I am unconvinced of the value or wisdom of publishing this, just as I am wary of the cult of self-expression, or the belief that one’s life and one’s feelings are in themselves important or interesting. Hopefully there is something more than that here; in any case, the urge to write about it is also an urge to communicate.

But this is also something of an exorcism. Since this happened, I have found myself unable to write anything of particular seriousness or complexity without returning to this subject; thinking about death when I should be editing a paper, when preparing a radio show, when proofing a book. This, I hope, presages some kind of shift: committing it to some final form is itself a blow against the sapping apraxia induced by the weight of death.

These essay fragments will contain content a reader might find triggering or upsetting. They have not been easy to write, as they sometimes involve an attempt to dwell in things one tries to shut out of mind, either by failing to address them or drawing them into an overhasty false conclusion. If there is a thread that runs through this, it is the attempt to understand certain of the effects of grief, frame them through politics, psychoanalysis and literature, and perhaps try to understand how they can be transformed. This effort is necessarily incomplete.

1.

I am trying to mourn you and I am failing.

I burst into tears on the bus today. It’s the second time in as many weeks. It activates the only behaviour I think of as peculiar to London, where everyone looks away while trying (discreetly) to see what’s going on at the same time. It’s unoriginal to say that shame is basically an economy of looking: that it is shameful to draw others’ eyes to yourself against the normal course of attention in public, that they in turn are trying to spare you shame (which would merely compound whatever distress you’re already experiencing) by fixing their eyes firmly on the unremarkable adverts passing the windows. They know (and you certainly know) that there is something dreadfully wrong, and that everyone around you has noticed it, but for any of us to act on it would risk distending the normal compact of daily life to breaking point, and thus heap further shame upon shame. In any case, such attention would do little to dry your tears, which are nothing to do with the people on the bus, who have doubtless many tears of their own – hence, they know to see and not see at the same time. I am trying to mourn you and I am failing.

I was told of your death by email. In fact, I should say suicide instead of death, but I find myself avoiding the word, as if I could soften the violence of it retrospectively by denying it purchase in my language. I choose euphemism to spare those who loved you the yoking together of your name with the belly-deep feeling of despair and utter loneliness that comes with the word, and all the last desperate images that come in association. I don’t know if that’s an act of mercy and self-preservation, or if it’s just a way of letting us all off the hook, denying you even that last agency. It could be both. Email is a cold medium, and I was doubtless colder when calling others to tell them. I was cold when I spoke of you to my boyfriend, when I got the news, and when I explained we’d not really talked in a while. I didn’t sleep well that night, and my grief started to seep out of the edges of my speech. I tried talking of other things, avoiding the matter, avoiding the honest despair at the edges of sleep. That sort of stupid resilience is how one ends up crying on buses.

In the absence of proper mourning rituals (which require both faith and an ability to name and quantify one’s relation with the dead, the latter to determine the proper period of grief, no luck here on either count) I find myself seized intermittently by the physical symptoms of grief: panic, shortness of breath, a sick weight behind the throat. I take to measurement. I measure the distance from where I’m sitting to where your funeral is happening: 5454.98 miles. I look at photos of the cemetery chapel. I think of your mother (whom I have never met) burying her son. The line between where you are and where I am is virtually half the globe, and you are dead.

I find myself uncertain of things I took for basic truths, as if something central to the stability of meaning in the world had vanished. I know this cast of mind is something to do with grief, but I can’t reason it out, because the tools of reason go wild here. The compass spins crazily. Grief warps spacetime.

On a piece of paper I write questions about this new place. How to get through it? How is this survivable? What made you do it? Could it have been averted? How do I go back to what was before? What were you thinking? How to make sense of it? How can I mourn you? They multiply. You understand, the particular difficulty of grief isn’t a denial of fact, but making that fact fit in the careful fabric of our world, without it tearing a rent in it. When I was a kid, I read that a spoonful of the substance that makes up neutron stars would be enough to drop right through the floor, right through the earth’s crust, the mantle, enough to cannonball through its molten innards and burst through the other side. So where do you put it down? I tear up the paper into tiny pieces, reach out of my window, and drop them into the air.

2.

Writing about suicide is dangerous. Among its many risks are: falseness of rhetorical presentation; the imposition of meaning on an ultimately meaningless event; saccharine or unduly sentimental memoir; yielding to glib but profound-sounding ‘truths’; the use of death as a proving-ground for the soul; to demand a redemptive element, or invent one as needed. Journalistic precepts for reporting suicide abound: avoid glamourising it, discourage overidentification, exclude details of method. Also to be avoided: trite links to mental health, mechanistic recounting of disadvantage or misfortune, in fact, best leave out causal reasoning of that kind altogether. A cluster of warning signs: hole in the ground, no-one knows how far it goes down.

I began this essay by writing to J, as if I were speaking to him, as if to begin to account for his death required that form. It is a kind of mourning for unfinished conversations. But I worry about this as a kind of rhetorical falseness, one that keeps open the wound of grief, that his close textual presence is a way of highlighting his absence. It risks also making him a saint, omitting the turbulence of our friendship, or suggesting that grief is simply a state of raw absence. To go beyond that state, I have to move to a more distanced style. These difficulties in style are, rather than irritating obstacles, symptoms of one of the paradoxes of grief. Most writing on grief will return to various metaphors about its unchartable space, its shapelessness, its odd ability to multiply, its changing weight – the feeling that it has in some way become the very stuff of existence, even as outward forms of life continue the same. Against this levelling sense there exists the urge to understand, name and represent grief, or at least the intuition that such an endeavour is possible and even necessary. It is from the tension between the two that I write this.

I also write because I want to expiate my guilt. Ten days before J’s suicide, he tried to Skype me. It was late at night, I was working, and hadn’t even realised I was logged in. I let the call ring out. Of course, I remembered that the last time we’d spoken he had seemed so paralysed and how helpless I felt. I’d been annoyed that he seemed unable to take even basic steps, perhaps more annoyed than justifiable, as his talent for self-sabotage and self-pity reminded me of myself at my worst. Regardless, I ignored the call. 1:13 a.m. – computers preserve one’s faults with precision – ‘Are you around?’ – I chose not to reply. Rationally, this ought not weigh immovably in my mind. His death was not visible from there, the casual phrasing hardly calculated to give alarm; I could not have known (I tell myself) and therefore I ought not feel guilty. (Do I really believe I could not have known?) Yet I fantasise about what I might have said had I been less self-involved at that moment. It is unreasonable to attach absolute moral significance to this moment, to insist on imagining all of the possible alternative paths that were foreclosed by it, but nonetheless I do. Insisting on the smallness of this moment, its insignificance, does nothing to dissolve it. Reason is sometimes inadequate to grief, and to guilt.

This keeps me awake at night.

3.

Joseph Brodsky once wrote that grief and reason, ‘while poison to each other, are language’s most efficient fuel.’ He was reading and thinking about a Robert Frost poem, about the animating antagonism between the two modes, but in a moment of unusually intimate psychological speculation wonders if Frost was reaching for this ‘indelible ink’ of poetry in the hopes of somehow reducing its level. Brodsky leaves this question of motive hanging at the end of his essay. Can writing marry reason to grief, can it make grief habitable, can it attest to something beyond the fact of desolation? Brodsky seems to want to say that it can, while at the same time saying that the further one dips into this ink the more endlessly it brims over, stains the fingers, engulfs the mind. I have been brooding over this contradiction (that writing reduces the inner level of this black substance, but that writing also multiplies that substance so there is ever more of it) and the puzzling fact he does not see the contradiction, for some days. He goes on to suggest that the poem itself may manage to transcend the seeming limitlessness of grief and the blundering uselessness of reason without compromising either position, like a little machine for catharsis at several removes. But I find this insight commonplace compared to – in fact, I suspect it is a deliberate closing-off of – the earlier ethical intuition that writing might serve to reduce grief, the fear that it might more deeply implicate one in that grief, and the compulsion to undertake it regardless.

I also find myself thinking of a very famous passage from Middlemarch on the nature of everyday tragedy:

That element of tragedy which lies in the very fact of frequency, has not yet wrought itself into the coarse emotion of mankind; and perhaps our frames could hardly bear much of it. If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence. As it is, the quickest of us walk about well wadded with stupidity.

This passage is most often quoted shorn of its first sentence, perhaps because of the beauty of its second sentence, but its moral argument lies there: that our stupidity preserves us not just from the intensity of the world, but from a keen appreciation of the devastation that walks in the street next to us every day. It is not a simple argument about the limitation of the physical senses, but that the limitation of our moral sense and our comprehension of the ubiquity of disaster allows us to continue to live. In our keener moments we are unsettlingly aware of our dependence on this blindness. If I were to extend this description to the territory of grief, it would be to say that grief tears away our careful insulation, renders the world much sharper. One becomes aware of how commonplace tragedy is, how countless people at any given moment must also feel as if the ground has dropped away beneath their feet. Eliot’s moral acuity here is not comforting: that some coarseness is necessary to move through the world does not make individual acts of coarseness excusable; insight does not cancel our moral responsibility, even while recognising its imperfect exercise may be all we can muster, and inevitable in its own way. It does not, for instance, mean that my answering or not answering a phone call is a matter of historical caprice, regrettable but morally void. The great novelist would upbraid me for my vanity here, the idle hint of a logic of ‘special providence’: she was a better anatomist of despair than to believe that its course could depend on one event alone. Nonetheless, the guilt remains.

I know J would roll his eyes at the way I’m going about this, using literature to think through grief. He’d want to know what I really felt, rather than what others thought. He was suspicious of too much adulteration. But I am sceptical of the potential for unmediated self-expression, and, moreover, I need guideposts while thinking through this grief. I don’t mean reading for sentimental cullings from sententious idiots, a weak and sweetened gruel for the soul, but to understand how others have marshalled the power of representation against grief. On the one hand we are dealing with a relatively universal phenomenon, death and grief, on the other something less common, death by suicide. Beyond this, there is the complicating factor that it is his suicide, and the intuition that suicide is not a kind of death of the order of other deaths. The role of volition marks it out. It follows that there are particular forms of grief that arise in this context. One must grapple with the uncomfortable reality of it: that it feels cruel, even while wanting to vacate any question of blame or fault. Of course, one might know rationally one’s death might damage or permanently wound others; we know that terrible moment is not occasioned by the conviction it has no adverse consequences. I know there is a calculus at work whereby the possibility of exit from one’s despair seems to outweigh both the terror of oblivion and the pain one’s death might cause others. I know this because I have made the same calculation, and never have I been more convinced that my results were different only as a matter of chance. One reason I am trying to think through grief and death is that to leave it unthought is to risk the worst parts of my depression returning; I also know that I’m walking along the seam of it while writing this, and my insistence on figuration and comprehensibility may finally be inadequate to stop its return.

Maybe what is so comforting about the great 19th century authors is their omniscience, and their readiness to make moral judgements. Some years back, it was fashionable to object to Eliot’s intrusive narrator, but, quite aside from the astringent wisdom of her interjections, it is some comfort that the characters are absolutely knowable: their errors and self-regard and avarice are not mysteries, their mechanics may be uncovered to our narrator’s unflinching eye, even as they remain obscure to the characters themselves. In the case of a suicide, such a claim to the possibility of knowledge is comforting only in that it promises some respite from the dreadful things we do not know. It is comforting even if it cannot be fulfilled; it is dangerous because it invites speculation. Several times in the small hours of the morning I wonder if J left a note; whether, if he left a note, I would want to read it; how it would likely obsess me (though, at 4 a.m., relative levels of obsession are moot.) I understand he did not; in turn I wonder, sleeplessly, had he written a note whether the act of writing would itself have dissolved the impulse.

4.

In the absence of a note, I search out statistics on suicide. The ONS tells me just under 6,000 were registered in 2012, points out the difference in rate between men and women (but says nothing of the ratio of attempts, which differs conversely.) It provides a breakdown by method (distasteful) and region. The trend is downward over decades, but rises more recently. The US rate is more-or-less equivalent. We understand that what is aridly called “health and economic inequality” (read: class, race) is a substantial factor, and that gender expectations, too, play an important role. The statistics on LGBT suicides don’t need repeating: we know them too well. The governmental suicide prevention strategy reads like an elaborate hedge around this absence of understanding. Momentarily, I fear dissolving the specific pain of J’s death in the anaesthesia of statistics, as if it would be traitorous to search for marks of commonality in suicide, as if it were somehow better to leave each death beyond understanding, interpretation or redress.

Historically, suicide has been interpreted as a political act in which the dead body either redresses or mobilises a system of social shame (most often in the ancient world), or, more recently, as a consequence of individual pathology. The former, where it does occur today, is usually interpreted as concealing the ultimate, pathological, cause; political motive emerges from neurochemical maladjustment. Had they sought help, had they had the right medication, had they availed themselves of the many nostrums on how to adjust, both the pathology and the politics emergent from it would simply evaporate. Perhaps that is true. But the numbers suggest otherwise, that this kind of death is unevenly socially distributed. Hard ground: I hold that medication is key to many people’s survival, but that medicalisation and the individualising nature of contemporary thinking (which also carries the tang of personal culpability for illness) obscures social factors in mental illness. In essence, as I would tell J in life that all of his life was political, so too I must insist his death is not only a personal disaster but indicts the society in which it occurs.

Yet the invocation of politics still feels hollow. So I may add J’s name to the charge-sheet, already so long and so bloody. Whether one might make a politics out of grief is a question without an easy answer. Certainly, refusing promises of its easy redemption, grief might be boiled down into an uncompromising rage, might anneal all the particular stress-lines and flaws of a person, make one into a militant of revenge. One might, conversely, become a living testament to the wounds of grief, hoping the display of its marks will shame society into changing. Both possibilities attest that people are permanently altered by grief, and perhaps the grief pertaining to suicide in particular, but this fact of permanence is the beginning of a politics of grief rather than its fullness. Desiderata for a politics of grief are many, from structural alterations in healthcare access, to cultural destigmatisation, to according to the grieving person a better treatment than mere terrified silence. I take for granted that such a politics would seek to generalise a sense that suicides are preventable, but that our current society regards them as either a matter of private pathology, or an unfortunate by-product of a generally well-functioning system of work and political order, rather than as they actually are, a symptom of a more widely destructive and miserable social regime. In that sense, it might merge with a general anti-capitalist politics. But we have come very far, very quickly here. Though this framing helps us understand J’s suicide a little better, it does less to deal particularly with grief, which, it is assumed, will fuel and be transformed or attenuated by political activity. Such an attitude is beset by possibilities for self-destruction and self-abnegation. In separating out the political framing of suicide from grief itself, I insist that the political framing is quite separate from and not dependent on grief (and therefore not to be regarded as a temporary conviction founded in mourning), and that politics itself may not be sufficient to transform or confront grief – even as it is so often the catalyst and precondition of explosive political movements.

This political framing of suicide is a form of representation: it represents suicide as collectively comprehensible through a series of more-or-less mechanistic psycho-social factors, and in response articulates a framework of analyses, demands and action supposed to stop them at their root. It is the highly rigorous, rational version of politics in its ideal type (its real world variants are messier) and a necessary but limited response. As a mode of harm reduction, it positions suicide as a social ill, grief as an undesirable effect, and seeks to obviate their causes. Such representation does not deal directly with grief and even sometimes seems to call for its repression; it can also be ruthlessly deindividualising, operating as it does by large-scale trends and the use of specific, personal deaths as general political symbols. At times, this feels ethically inadequate, even a violation. As such, it might well be a category error to look to politics as a way to understand grief: that is simply not what politics does, or politics is even the repression (or sublimation) of grief, rage and vengeance. Politically understanding suicide seems vital, because what happened to J (unemployment, devaluation, poor medical treatment, intermittent substance abuse) is eminently political; however, political understanding, or even propositions for political change, are insufficient to touch that encroaching, overspilling black ink of grief of which Brodsky wrote.

5.

If politics is traditionally concerned with the general order of a shared society (literally the city or polis) then it holds that there are certain experiences that are pre-political, or pertain to the private sphere. I am convinced of the arguments that say this division is ultimately unsustainable, and conceals a further and larger politics; however, that this division exists indicates that political reason is only capable of dealing with things according to a certain logic. So it might bring forth from grief a grievance, and seek its redress or compensation, or explain the hidden social logic of that grievance, but say little and do little about that originating grief. In part, I suspect this is because most kinds of political thinking deal in substitution: that for this grievance there should be that kind of and amount of redress. The point of grief is that it is not subject to that kind of substitution, and to attempt to address it according to that logic is to invite endless failed attempts to find a proper substitute, a reiterative process of improper or inadequate substitution, the deferral of grief or its transformation into obsession or reperformance of loss. (I think this question of substitution and reenactment is fundamental, and recurs in many cases of loss or injury other than death.)

I am also interested in the metaphors we use to talk about grief. These are so deeply set in our language that they seem natural, and we use them without a second thought. One I mentioned above was the shapeless weight of grief – the word ‘grief’ is ultimately from the Latin for that weight. Another is the metaphor of work. If grief is a weight, then we must work to move or reduce or change it. (It does not move of its own accord: dead weight.) Hence in the folk-psychologies surrounding grief one is held either to be or not to be ‘working through’ grief properly, and the various tasks of which this work is composed involve ‘accepting’, ‘understanding’, ‘confronting’, ‘letting go’ and so on. If I sound contemptuous of this pop-psychology, it is only because it is sometimes used to cause great distress to those grieving ‘improperly’, with all the moralising that typically surrounds matters of work. In fact, it grasps some fundamental truths about grief: that it invites being thought about physically and spatially, that it is an experience that involves something internal being damaged or lost as well as something external, that some fundamental action of holding on and releasing is involved. The closer one looks at those tasks, however, the less clear they begin to seem. If this popular wisdom simply encodes long-held common intuitions about grief, then its central metaphors owe at least something to a 20th century diffusion of Freudian ideas.

In 1917, Freud wrote ‘Mourning and Melancholia’, in which he opposes the normal state of mourning (the ‘painful unpleasure’ in which we gradually disinvest psychic energy in the lost object) to the pathological state of melancholia (an inability to detach, and instead a psychic incorporation of the lost object, where the ambivalent love and hatred felt toward it is now directed against the split ego.) Despite Freud’s best efforts, none of his arguments distinguishing between normal and pathological states of loss completely manage to seal one off from the other, and by 1923 (in ‘The Ego and The Id’) he prefers, given the ubiquity of melancholic identifications and incorporation, to view it as vital in development of the superego (and views the father, unsurprisingly, as the primary object of incorporation.) But what of mourning? What happens later in life, when people die? One useful extension to Freud’s thinking here comes from Melanie Klein, who argues (in ‘Mourning and Its Relation to Manic-Depressive States’) that mourning is melancholic, and though the process of incorporation is vital to the articulation of the psyche in childhood, loss and reintrojection is a process repeated throughout adult life. In each case, the loss imperils the inner world of ‘good objects’ with which the healthy adult has populated his psyche since the initial loss of his caregiver in infancy:

“His inner world, the one which he has built up from his earliest days onward, in his phantasy was was destroyed when the actual loss occurred. The rebuilding of this inner world characterises the successful work of mourning.”

The ability to reestablish this inner universe distinguishes the successful mourner from both the failed mourner and the ‘Manic-Depressive’ in Klein’s terminology. In this particular lineage of psychoanalysis, it is this concept of the inner world that I find most suggestive, especially the way in which it parallels my concerns with figuration; that this particular exercise of reason is an attempt to rebuild that inner world. What distinguishes Klein’s account of mourning is that each loss re-endangers the whole of the inner world: with this death, all the others that preceded it, again. What Klein does not say explicitly, but I think follows, is that the losses may finally be too many to return from, the mechanisms that allowed one to rebuild the inner world last time may not be strengthened but rather depleted, and this time around finally inadequate to the task. In the case of grieving a suicide, is this doubly the case? The violence of suicide, and the thought that J would have himself been experiencing that absolute shattering of the inner world, makes it difficult to ‘complete’ mourning.

I assume the inner dynamics of my psyche are not likely to be easily discerned by me – blocks, cleavages, divisions, repressions, these are the words the literature uses to describe the normal state of inner opacity that shrouds our waking mind. Neither do I think Klein’s model of the mind is its final and best description, but close enough to a good recension of the desire and despair that characterises mourning. Its semi-mythic dimensions – the shattered and rebuilt world – are not digressions from scientific accuracy, but expressions proper to the magnitude of grief and its deeply personal, yet universal, attachments. Something more, then, is needed beyond this description; strategies for rebuilding the inner world are short on the ground. Merely urging oneself to rebuild or restore does little, however ferocious and demanding the tone struck. Given this inner opacity, I must trust that my instincts (in this particular case, rather than universally) are presenting me with some method of reconstruction, however winding and strange its paths may seem. My instinct, above all, has been to take up certain poems, novels and plays, and to think about them, thinking with an intimacy and closeness – a kind of critical intensity, perhaps desperation – that I have hitherto rarely experienced.

6.

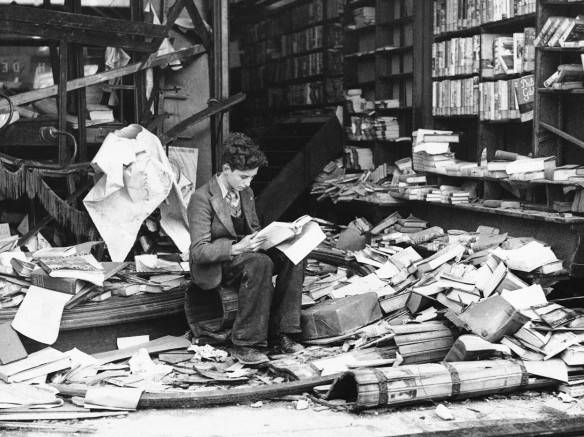

What is this urge? It isn’t simply the urge to experience art, but to think about it, to respond in a way sufficient to it, which does not diminish it through coarse interpretation or betray whatever it stirs in me. It is no longer possible to hold the preposterous opinion that certain works of high culture have an intrinsic moral power which improves their audiences: the opera-loving concentration camp guard is but one of many figures of the twentieth century that makes this idea ridiculous. Therefore, I cannot believe that there is any guaranteed easily redemptory route through literature; I do not seek to repopulate my psyche with Lear or Orestes or Antigone. Nothing so easy: they are not people, still less people one would want nestled in the most private corners of the soul. Similarly, the urge to think about these texts is not to extract from them a series of pat remedies for inner affliction, but an expression of that paradoxical inclination to reason in spite of grief which has so preoccupied me. There is no guarantee that it will help, but its method of reasoning – attentive, unsparing, as involved in the minute particular as the vast context – seems to me a model of the kind of thing that might help restore the world. If there is a secret link between mourning, memory and representation, I think it is seen – faintly – in this unstinting attention.

A caveat: it might be simply that I am so trained in the habits of literature, so conditioned to think about it, that this becomes my only way to work on grief, attempting to transform it by exposing it utterly to this art. It differs from rending one’s clothes, drinking oneself into a stupor, burying oneself in work, only in that it promises the possibility of its confrontation, transmutation. The possibility of something more than temporary deferral. Not the guarantee, the possibility. These are unfashionable things to say about literature, both in the magnitude of possibility ascribed to it, and in the awareness of how prejudiced and parochial our canon seems. My grief canon is not in that respect unusual: some modernist poets, poems from Milton and Jonson on the death of loved ones, Donne’s incredible poems of arrogance and mourning, Catullus. Some perhaps more unusual critical works. Longinus’ confused treatise on sublimity. Virtually no novels, except one. Plays, however: the Greek tragedians and Shakespeare. These last have particularly preoccupied me.

Longinus, first, briefly: ‘On the Sublime’ is one of the earliest examples of literary criticism. Longinus has identified that particular works of literature evoke a strange pleasurable discomfort, almost a kind of vertigo, in their reader. He wants to know both what it is, and how it is produced. On the latter, he finds various hallmarks that produce this effect (and is surprisingly generous in comparison to one’s prejudices about the ancients and what they thought good) but has more difficulty pinning down the former. He recognises that again and again, works of literature seem to coimplicate us in their intensity, that they somehow produce an experience of alienation and identification, an encounter with a greatness that is hard to encapsulate (such an encounter need not be intrinsically good, though Longinus clearly wants it to be). Struggling for a way of expressing this sense of vastness, he says that sublimity is ‘the echo of a great soul’, as if this greatness which cannot sufficiently be explained in terms of the mechanics of the text therefore must be located in the moral grandeur of its author. We do not adhere to so easy an explanation today – great authors are no less morally frail and injured than the rest of us – though some persistent sense of a greater access to truth remains hard to extinguish. The incomplete but meticulous explanation and the elusiveness of sublimity itself are good beginnings for literary culture, good principles for thinking about what literature does to us and how, aware of the limits of explanation without abandoning it.

Sometimes I think that Longinus is exemplary of one of the central questions of our culture, which is how things act on each other over distances and times. This question, which provided an organising principle for the natural magicians and proto-scientists of the late renaissance, is no less an animating question for literary criticism. How can something written 500 or 2,500 years ago express something that leaves me feeling not only profoundly moved, but as if I have been exposed to something true in a way that everyday life does not often permit? Explanations here tend to grasp for some universal feature of human existence. Otherwise, people reach for a modified version of Aristotle, and say that these great works allow us to safely purge our emotions (catharsis) as if they were a built-up static charge. But somehow this semi-biological explanation has always seemed least adequate in the face of great stories of loss, tragedy in particular, where the sense that something is being taught us is never far away. (Imagine a future society in which a device or a drug had been invented to allow us to express and discharge grief in an evening, with no subsequent ill consequences. Would we feel something missing?) That it is fiction helps; there is a profound difference between a tragedy and a snuff film. Beyond that, I think that most of the most successful tragedies do not offer something simply redemptive, but take place at the intersection of justice with revenge, stress (sometimes until breaking point) the idea that one person might be substituted for another, reveal that the institution of law never perfectly supersedes our excessive and scarcely satisfiable appetites.

But even that is too broad an abstraction. Perhaps it is merely the fact of mimesis, that the human imagination can seemingly compass and represent such things, that allures us. The only novel I have found to talk directly of suicide without being useless or crass or vapid is Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian, which is just such a feat of imagination. It is (to my mind) one of the very greatest novels of the twentieth century, although it is preoccupied with things that seem apparently remote from us. The passage that I have come back to again and again is that of the suicide of Hadrian’s young lover, Antinous, and the emperor’s subsequent grief. Antinous joined Hadrian at a feast, attired in a Syrian robe, ‘sheer as the skin of a fruit’; joy shines out of him. Later, in bed, Hadrian wakes to discover Antinous’ face covered in tears, but the agony is private, and Hadrian returns to sleep. In the morning, Antinous disappears, drowned in the Nile as if a sacrifice. On realising this, Hadrian says:

Everything gave way; everything seemed extinguished. The Olympian Zeus, Master of All, Saviour of the World – all toppled together, and there was only a man with greying hair sobbing on the deck of a boat.

This is the most succinct expression of grief that I know: the simple observation that in grief everything gives way, all pretensions one had to composure, or to grandeur, all the vain and indulgent claims to wisdom or vision, all cherished things that make up our world. It is not the formal claim to these titles that has vanished (Hadrian is still emperor, for all that means), but their animating substance, the connection they had to the real world is ‘extinguished’. They begin to feel absurd. When Hadrian feels himself stripped to ‘only’ a man, that ‘only’ does not mean simply smaller in stature and depth than his ridiculous titles would suggest, like other men, but also that he is suddenly utterly alone in his grief, alone and himself mortal (‘greying’) with all things stripped back to loss.

This collapse of meaning, the sudden absence of the connections that make one feel really in the world is a commonly attested feature of both grief and depression. When I say that suicide is a death not of the order of other deaths, I mean that in all other kinds of death there is some division between the cause of death and person who dies; only in suicide do we have to come to terms with their terrible unity. It repeats as a terrible and obstinate fact. We have some measure of this in a subsequent passage:

Antinous was dead. I remembered platitudes frequently heard: “One can die at any age,” or “They who die young are beloved by the gods.” I myself had shared in that execrable abuse of words; I had talked of dying of sleep, and dying of boredom. I had used the word agony, the word mourning, the word loss. Antinous was dead.

Love, wisest of gods… . But love had not been to blame for that negligence, for the harshness and indifference mingled with passion like sand with the gold borne along by a stream, for that blind self-content of a man too completely happy, and who is growing old. Could I have been so grossly satisfied? Antinous was dead. Far from loving too much, as doubtless Servianus was proclaiming at that moment in Rome, I had not been loving enough to force the boy to live on. Chabrias as a member of an Orphic cult held suicide a crime, so he tended to insist upon the sacrificial aspect of that ending; I myself felt a kind of terrible joy at the thought that that death was a gift. But I was the only one to measure how much bitter fermentation there is at the bottom of all sweetness, or what degree of despair is hidden under abnegation, what hatred is mingled with love. A being deeply wounded had thrown this proof of devotion at my very face; a boy fearful of losing all had found this means of binding me to him forever. Had he hoped to protect me by such a sacrifice he must have deemed himself unloved indeed not to have realized that the worst of ills would be to lose him.

I do not want to over-analyse this passage; as it is I find it hard to type out without being moved to tears. The mechanics of J’s death and the fictional Antinous’ are hardly similar; nor are the relationships the same. Yet this is the best description of that intimate grief that I know. It describes the obstinate recurrence of fact (‘Antinous was dead’), the feeling that one never knew the real content of words like ‘loss’ until now, the hollowness of platitude, one’s implication in death, and above all the keen and unremitting awareness of the precise balance of despair and love, the reverberating violence and hopelessness of suicide.

This is grief, then. Yourcenar’s text is very fine on the ‘strange labyrinths’ of grief, its sudden return when one thinks oneself finally consoled. One of its defining features is the collapse of meaning, the sense that the coherence and point of the world is lost in the face of death; this is like the catastrophe of the inner world Klein talked about. I have also suggested that one of the constituent features of grief and trauma is re-enactment, that this repetition can become a sign of an incomplete mourning. On an intellectual level, this becomes the conviction that the most authentic position, the vantage-point that most corresponds to the truth of the world, is one in which all meaning has rotted away to be replaced only with death, and one’s involvement with death. I want to see how one might go beyond this.

7.

The two writers I have been returning to over and again to think about a way of going beyond grief are Euripides and Shakespeare. Of the Greek tragedians, to look at Euripides in this way might seem strange. He is a sharpener of already desolate situations: it is Euripides who invents the story of Medea actually killing her children. (Before, she just abandoned them to die.) His proper study is how grief and rage sharpen people into monsters, the failure of institutions (marriage, parenthood and family taboos, government, religion) to restrain his characters’ slide into violence and degradation, and how those institutions in fact generate excess and destruction. Euripides was living in a period of catastrophe and never-ending war, perhaps far enough advanced to suggest to him the civilisation he knew would never be recognisable as itself again; his characters always seem to be picking their way through the ruins of greater times, greater men. Maybe this accounts for his attraction today.

Though I have been reading all of the tragedies, and Euripides’ especially, there is not much on suicide that is useful. Helen, in his play most concerned with noble suicide, thinks Ajax’s suicide a kind of madness. Herakles rejects it. Polyxena, who willingly embraces her role as blood sacrifice, disappears into nothingness as her death fails to make the winds rise. My interest, however, is in a play very different to most of Euripides’ surviving work, Alcestis, and the resonances it has with a far later play, Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. Alcestis isn’t a tragedy, though it isn’t a comedy either. It is a revision of an ancient story (probably one of the most ancient, in its simplest form) about a woman who sacrifices her life for her husband, by taking on a fate pronounced for him, and by her death secures his life. In some versions the sacrifice is refused, or by some contrivance the wife is rescued from the underworld, and they are reunited in life. In this case, it is achieved by the intervention of Herakles, who stumbles into the house of Admetos shortly after Alcestis has taken his place in death. Herakles, buffoon and demigod, embarrassed at having forced Admetos to interrupt his mourning to welcome him, goes to her grave, wrestles with Death, and returns a veiled and silent Alcestis from death to life.

It isn’t hard to see why a story where someone returns from the dead might appeal at the moment. But what does Euripides do to this basic fairy tale? He adds time to it. The trickery used to save Admetos’ life has taken place some years before, and the play begins on the day appointed for Alcestis’ death. Already one element common to many tragedies is present here: some long-feared past debt now returning with inexorable consequence. It is possible, at this point, to exit the theatre or put down the playbook thinking of nothing more than how nice it is to see disaster give way to joy, of Alcestis’ perfect and noble sacrifice, and cherish the fairy-tale ending all the more for its impossibility. But one can’t help pulling at loose threads. Is there something unpleasant in the way Alcestis gets exchanged between her husband, his guest, and the underworld? In some of the old versions of the myth, Alcestis chooses to die in her husband’s place because he is a good king, presiding over a kingdom of peace and prosperity and beloved by the nation. So who is this vain bore speaking in cliches while she lies dying? Is it possible she has chosen an inadequate object for her affections. One might accept that a sacrifice consummated at the moment it’s proffered would admit no doubt; by introducing this gap, Euripides allows time for it to grow. Suddenly you think back to her speeches and wonder about the almost immaculately repressed doubt sweating through them.

My point isn’t that Alcestis is concealing something sinister under the fairy-tale, its secret truth. After all, the dominant tone of the play is of disaster miraculously averted, of that strange word charis, which means favour, gift, grace. It is that the unsettling elements of the play, the questions of worth, are right there alongside it. Circuits of commensurability and incommensurability criss-cross the play. Alcestis is eminently replaceable (else why extract a promise not to remarry?) but her act of substitution unrepayable. Death simply wants a life (quantity: one, date: overdue). Pheres has no interest in substituting his life for his son’s. Perhaps most unsettlingly, Admetos wants to make a statue of his dead wife, lay it in his bed at night, and embrace it in her place. This logic of substitution is also a common thread of tragedy: who may be substituted in place of whom, how revenge or restitution may be taken. The discomfort of these questions of worth and exchange is doubtless what leads many later adaptors either to improve Admetos’ character or render him innocent of involvement in Alcestis’ choice: there’s something uncomfortable about Euripides’ characters. At the end of the play there is a singular a coup-de-théâtre, the veiled Alcestis returned to the stage, silent, revived from death. The sheer physical power of this moment must only have been enhanced by her silence. And yet: why is Alcestis silent? Euripides puts an explanation – ritual purification – in the mouth of Herakles, but it is still the writer’s choice. Can a woman who has died and returned be the same woman? The play tells us it is so, but Alcestis’ silence remains obstinate.

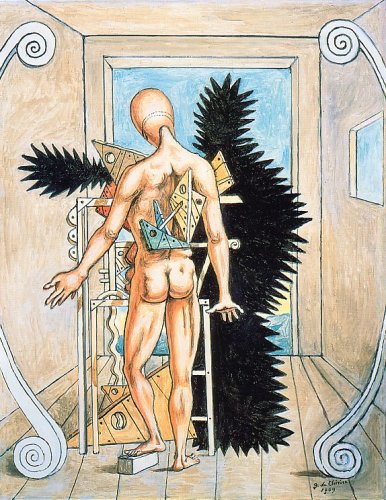

I have dwelt on Euripides, and Alcestis in particular, partly because the questions of worth and catastrophe preoccupy me at the moment, and their presence alongside and inside the consolatory fairy-tale. But I have also always felt a strong connection between this play of Euripides and The Winter’s Tale. In obvious ways, of course: the statue, the return of the beloved from death, the silence (Shakespeare likely read Alcestis in Buchanan’s 1556 Latin version). But less tangible connections suggest themselves: the strangely composite form of the play reminds me of Euripides’ departures from his predecessors. Most of all, however, it seems to me like Leontes is a character who has walked out of a Euripides play. The madness that afflicts him in the first half of the play, his inability to see anything but corruption, deception and baseness in the world around him, the way in which that allures and repels him, seems like that crisis-world in which Euripides’ characters circle each other. Something has eaten away at Leontes like an acid: he has suffered a collapse of all he thought guaranteed in the world, and can see only the possibility of its untruth.

It is not unusual for Shakespeare to drop characters into worlds to which they do not belong. Othello, for instance, is the story of a grave man in a comic world, from whom the gulling and confusion proper to comedy draw a tragic result. Beyond this, however, the tragedies (or at least, some of the characters in them) participate in a fantasy of time rewound: revenge tragedy is the clearest instance of this, where some equal slight, some equal injury to some equal person, might serve to redeem, renew or annul the past. It never does, but absence of result has rarely halted propitiation, especially from the desperate. I mention these themes – generic discord, the logic of substitution, the fantasy of time rewound – because The Winter’s Tale confounds their usual deployment in the service of a miracle.

After J died, I did not read for some days. When I did pick up a book, it was The Winter’s Tale, to read quite deliberately Paulina’s speech of awakening as the statue of Hermione is returned to life. At the time, I could not bear to read much of the play – bequeath to death your numbness – but the compulsion to return to it has been consistent, and all of my reading of late has led me back here. Let us remember what has happened in the play: Leontes’ madness and jealousy has caused him to accuse his heavily pregnant wife, Hermione, of infidelity with his best friend, putting her on trial for it and trying to poison him. Leontes’ son, Mamillius, dies of a wasting disease brought on by Leontes’ accusations against his mother. Hearing this news, Hermione then dies. In the interval between the onset of Leontes’ jealousy and her trial and death, she has given birth to a daughter. This daughter is taken and hidden away. Sixteen years pass. Eventually, Leontes is reunited with his now adult daughter, and taken to see a statue of Hermione, which turns out to be her, alive. Paulina reveals the living Hermione thus:

PAULINA: Music, awake her; strike!

‘Tis time; descend; be stone no more; approach;

Strike all that look upon with marvel. Come,

I’ll fill your grave up: stir, nay, come away,

Bequeath to death your numbness, for from him

Dear life redeems you. You perceive she stirs:

Start not; her actions shall be holy as

You hear my spell is lawful: do not shun her

Until you see her die again; for then

You kill her double.

The tonal shifts of this speech have always astonished me. It begins in the tones of the fairground magician, then pivots suddenly (on ‘Come’) to extraordinary tenderness and intimacy, then pivots again into giving instruction to Paulina’s immediate audience on stage, and by extension, us. We are immediately aware we are witnessing something deep and important, but what exactly? The late plays feature several scenes of recognition between families long estranged and the women thought dead, but only in this play are they merged in a single scene. On one level, the subsequent revelation that their daughter, Perdita, survives is a resolution of an anxiety about time, a reintegration of the family shattered by Leontes’ madness in the play’s first half: ‘this life / Living to live in a world of time beyond me’ as Eliot put it, thinking of another of those Shakespearean reunions. But why does that explanation feel only partial? We are not yet clear about what has happened in the statue scene.

Much critical ink has been spilt on working out exactly what is happening in this scene: it used to be taken for granted that it was a typological echo of Christian resurrection; as that interpretation receded, it has come to be seen as a theatrical miracle, with Paulina as impresario, Hermione having been hidden away for the intervening sixteen years. There is sufficient textual evidence for this position (e.g. 5.3.125-8) and it fits nicely with the late Shakespeare’s preoccupation with reflexive theatrical representation. But something chafes. That something is Mamillius. Coleridge remarked on the ‘mere indolence’ of Shakespeare’s failure to make any mention of Hermione’s concealment earlier in the play, instead of her death. Until she reappears as a statue, the audience has no reason to believe she is anything other than dead. After all, Leontes insists on seeing the bodies of his wife and son, and has them buried in the same grave. There is no theatrical uncertainty, no winking metanarrative, about these deaths: certainly if Mamillius is dead, Hermione is too.

Any way of thinking about the power of this scene has to account for it in terms adequate to the whole play: it must account for Leontes’ madness, and it must account for Hermione’s apparent death earlier in the play (and, in fact, her silence to him after her resurrection). It won’t do, therefore, either to read it as a Christian resurrection scene, or plead that the play as we have it is just missing a revision to make clear Hermione’s only seeming death. I think Cavell is closest to this when he reads in the play Leontes’ permeating, self-destroying skepticism, and Hermione’s redemption of this skepticism in what amounts to a wedding scene. It seems to me, in fact, that it is vital that an audience is as convinced as Leontes that Hermione is dead, that we do not know whether the actor playing Hermione is supposed to be a statue or the living Hermione disguised as a statue. That such an uncertainty is only possible on stage is the point: the theatrical wonder-working is the outward form of a dramatic miracle, but which has much more within it than simple fascination with the mechanics of theatre.

If in the first part of the play, Leontes is like a tragic character, unwilling and unable to properly interpret the world around him, then in this final act, the rules and logic of tragedy are upended. It is, after all, a winter’s tale, of some strange comfort in the dead season. As it opens, Leontes’ courtiers are urging him to leave his grief and remarry, but Paulina reminds him that Hermione is ‘unparalleled’: Leontes refuses that logic of substitution so persistent in tragedies, of course no substitute would be possible. In a sense, both courtier and Paulina are right: from the perspective of the state, Hermione is replaceable; from the perspective of conscience and person, she is not. It is evident that Leontes is obsessed by guilt and transfixed by death; the unaltered clay of the violent man is visible in his fantasy that the ghost of Hermione might induce him to murder any new wife. His grief has emptied him out into the memory of the departed, in a kind of living death, but his refusal of substitution is an important precondition for the play’s conclusion.

The act’s second scene, in which some chorus-like characters recount Leontes’ discovery that Perdita is his daughter, is equally important in priming the audience for the statue scene. Their reunion goes beyond description in language: ‘… there was speech in their dumbness, language in their very gesture. They looked as they had heard a world ransomed, or one destroyed.’ They even say the news is like an ‘old tale’, so strange as to defy expectation. Like so often, ancillary characters are audience substitutes, and the emphasis they lay on physicality and gesture, as well as events so strange they require metaphorical description, are indicators to how we are to engage with the final scene. This signposting continues in that final scene itself, where the exclamations of wonder emphasise that the stage-world is a largely realist one, in which resurrections of the dead are something strange enough to provoke shock; it is not the kind of thing to which they are accustomed. When one of the reporting gentlemen says ‘Every wink of an eye some new grace will be born’ we are again being prepared: ‘winking’ in Shakespeare has the sense of not seeing, or not seeing clearly, as well as the momentary closure of the eyelid. The proximity of uncertainty and grace, grace produced by theatrical deception, is the sense of that last scene.

So Leontes enters this scene still a man of death, hoping for some consolation in the life-like statue of Hermione; instead the statue comes alive, is indeed Hermione, alive and not dead. But the miracle here – the grace – is not in the resurrection itself, and Paulina goes to great lengths to protest the legitimacy of her art. The image of his dead wife ‘conjured to remembrance’ Leontes’ evils. He asks, ‘does not the stone rebuke me / For being more stone than it?’ After all, given his sins, there is no reason to expect a reunion with Hermione to be joyous; some interpret Hermione’s silence to Leontes (she speaks only to Perdita) to be such a rebuke. This misses the real miracle here, which is that of forgiveness and restitution. In the universe of tragedy from which Leontes comes, the physics of forgiveness do not make any sense, they are unthinkable: violence is met with violence, loss met with loss, no transformation of the situation is possible. What if something, for once, was different? If tragic characters are beset with a desire to rewind time, then Shakespeare now gives us a moment where just such a thing happens. Hermione embraces Leontes, she ‘hangs about his neck’. As the gentlemen have prepared us, there is indeed content to these gestures, language in this dumbness.

We have entered into this private chapel with Leontes, as sure as he is that Hermione is dead, perhaps even carrying about with us so much death, as much as he is. We are as unsure as he is whether the person playing a statue is also playing someone who is alive, returned from death in the kind of miracle only possible in theatre. What does it feel like for someone who has been carrying so much death about with them, such as that they feel like stone, to suddenly find the life of the world in front of them and embracing them? Our modern editors insert directions into Paulina’s speech, telling us to whom each section of the speech should be directed. No such directions exist in the original. Suddenly one feels that those low and intimate lines of her speech are directed not at Hermione, but at Leontes, and to us:

‘… stir, nay, come away,

Bequeath to death your numbness, for from him

Dear life redeems you.’

8.

The word ‘mourning’ shares the same Indo-European root as our word ‘memory’; in some small way these essay fragments are a memorial to J, an attempt to deploy reason against grief, to use reason to embrace grief and somehow transform it. When I try to understand art’s consolatory function, it is because I am desperately in need of it. When one emerges from the dark of the theatre at the end of The Winter’s Tale, there is no false sentiment or hope that one’s loved ones may miraculously return as living statues. The secret worlds are not regenerated. Yet something profoundly affecting has happened. It has not removed grief – the grief so many of us carry about like rocks in our pockets – nor transformed it exactly, but given us a presentiment of what such a transformation might feel like.

In rhetoric, there is a figure called prolepsis. It means that gesture where one anticipates something yet to come – an objection to an argument, for instance – in the present. In literature, we can sometimes call characters proleptic: Mamillius is one of these, where he seems to anticipate his death in his young, grave, speeches. Sometimes we say this is something that can only happen in literature; the text’s status as a made thing allows us to do things with time and apprehension that are impossible in real life. But I think we sometimes experience time this way, we sometimes experience the presentiment of a world as it might become long before it happens, even acutely aware of the distance between there and here.

Though the labyrinths of grief are strange and long, I want to try to use the power of reason, and representation, to record just such a moment of prolepsis. A while after J died, I went on a long-arranged trip. A few of us had gone out early to see the sunrise from the cliffs overlooking a wide sea. I remember thinking as the car shot down the road how weird and bare the landscape – thin plants and sand for soil, the kind of country Catullus might have crossed to stand at his brother’s grave – and the night turning from black to blue. The coldness of the air out on the cliffs. Thinking how preposterous and how arty to be thinking about death while waiting for the sunrise; thinking how in the wake of a death, all thoughts bend themselves toward death. The blankness of the sea’s expanse, its silence.

The sun rose above the horizon line: deep bruising blue, pink, red, then gold. As it rose the air transformed against my skin, its night coldness pierced by the sun’s warmth. In my chest, the heaviness rose higher and higher, as if propelled by some hidden chemical transformation. How absurd to be so transfixed by something so banal as a sunrise. The sun spread a path of gold across the water, a small sailing boat tacking just on the brink between the dark and the bright waters. Then even my skepticism dissolved, as if all my coldness and weight were burning up in that light. I watched the sun change its light on P., sat next to me, and he reached out to touch my elbow; I felt so briefly the whole world depended on that gesture, that in its absolute simplicity and tenderness it was as a reproof against death. My grief lifted, for just that moment: I saw what it would be to have that grief transformed utterly.

I do not know how to end these fragments: nothing can make J’s death right, or meaningful. I have sometimes suspected my grief to be improper or excessive; my guilt as much a fear I am subject to the same loss of meaning, the same kind of catastrophe. It is required you do awake your faith. If certain pieces of art have consoled me, it is not because they distract from death, but because they figure certain ways of thinking about big questions: what and how to live, and how to deal with death. They affirm that thinking such things is worthwhile, that it is possible to make things that profoundly affect and change people. None of this wipes away or redeems the past, diminishes violence or softens loss, but it promises loss is thinkable, bearable. It is required you do awake your faith. If grief is like being plunged into an alien world, full of darkness, then I find myself thinking that reason is reaching out to touch and describe that world, to discover in it contours and planes familiar and unfamiliar, hear other voices speaking in it, and other hands reaching out to touch yours. We might not ever find our way through the dark completely, but we may well find some way to live in it until the dawn comes. That might be as much a memorial as is possible.

![Anselm Kiefer, For Paul Celan – Stalks of the Night, 1998[?]](https://piercepenniless.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/kiefer_forpaulcelanstalksofthenight.jpg?w=584&h=389)